An International Conference on Urban Design

The ideal thing would be to have a good American

suburb adjacent to a very concentrated Italian

town, then you’d have the best of both worlds.

Colin Rowe

For the last half century, urban design has been devoted to the reappraisal and the regeneration of the existing city, considered in its traditional form as a dense, compact fabric. Research, design methodology and implementation in this vein have been significant from both a qualitative and a quantitative point of view.

During virtually the same period, however, the urban fringe – the light city or “ville légère” – was instead notoriously neglected as a subject unworthy of serious urban debate. This situation has arisen despite the fact that the lower-density zone, between the urban core or the dense periphery and the proper agricultural land has become a ubiquitous phenomenon in the landscape, affecting people around the globe. Different national and geographical contexts have resulted in a variety of configurations and organizations: from the formal suburbia, typical of the Anglo-Saxon metropolises, to the favelas and other illegal settlements in developing countries, to the semi-spontaneous, semi-illegal perimeter, mostly of onefamily houses of the Italian “città diffusa”. Until fairly recently, all have shared a common fate of being deliberately ignored or simply overlooked as having insufficient value or only marginal impact on the discipline or profession.

Main stream studies and criticism have supported a negative attitude towards low density settlements, considered costly, environmentally unfriendly and generally non-sustainable. Recent studies, however, have successfully critiqued this conventional wisdom and in so doing have propelled the debate between city vs. suburbs to new and promising levels of discourse.

Whatever the specific parameters of this argument may be, however, two circumstances cannot be overlooked. First, there is widespread pressure for urban sprawl due to powerful cultural, economic, social, anthropological factors. Second, official policies have tended to deny the underlying causes, which have generated this phenomenon rather than proactively addressing them. The urgent challenge will be, it seems obvious, is to offer solutions that are able to positively guide the making of low-density landscapes while addressing the same set of needs and desires, which made them attractive in the first place.

Most importantly, the conference organizers believe, the ville légère, suburbia, middle landscape, città diffusa, campagna abitata, arcadia, along with all the varieties that exist already have a relevant role in the morphology and in the functioning of metropolitan areas as well as in the ordinary lives of millions of people. In most cases, however, their performance is unsatisfactory both in concept and application. The complexity of the problem on the one hand and the unexpected opportunities on the other has typically been underestimated. Rather than adopting mere prohibitionist policies, it is proposed that contemporary urbanistics should study and implement regenerating actions through critical design efforts.

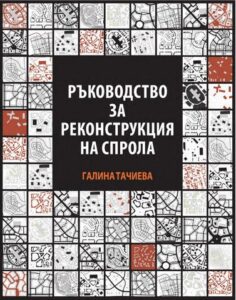

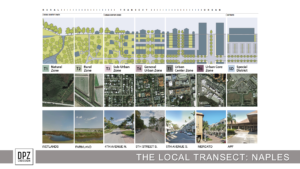

Today, several important contributions converging from different research and practice areas are beginning to emerge: descriptive and evaluation studies on sprawl; transect and other typo-morphological research and projects; sprawl repair and retrofit classification and case studies; densification and morphological and functional redevelopment; studies on lowdensity and garden city design; studies on lean urbanism. This is an ambitious and wide range of potential contributions, not too wide or ambitious, however, if one considers their profound relevance to urbanistics.

Ideally a more inclusive and comprehensive idea of urban design could offer to the “suburb” something comparable to the disciplinary production it has been providing to the “concentrated town”. Then you would actually have the best of both worlds.

of the Dr. John M. DeGrove webinar series, Galina Tachieva joined 1000 Friends of Florida to discuss the repair of sprawling communities. The structure of the webinar allows for over an hour of densely packed lecture, instruction, and Q&A to properly dissect the prevalent issue of sprawl in modern suburban communities across the country and around the world.

of the Dr. John M. DeGrove webinar series, Galina Tachieva joined 1000 Friends of Florida to discuss the repair of sprawling communities. The structure of the webinar allows for over an hour of densely packed lecture, instruction, and Q&A to properly dissect the prevalent issue of sprawl in modern suburban communities across the country and around the world.